Beauty is cultural, what is beautiful today was not beautiful before, what will be beautiful in a century may be very different from what we consider this way today. But it is true that today the general patterns of beauty are governed somewhat by what the ancient Greeks considered worthy of beauty. Yes, the perfect body and beauty were born was born in classical Greece.

We will speak today, then, of the source of beauty in our world: Classical Greece. There, centuries ago, our most enduring standards of the perfect body and beauty were born.

Classic Greece

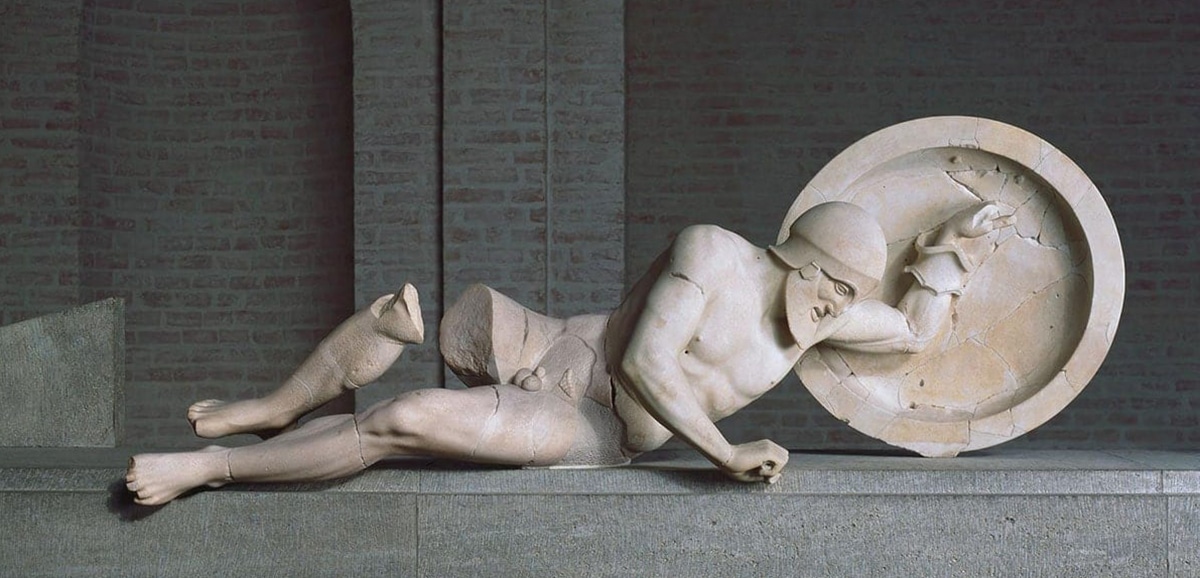

This is the name of the period in the history of Greece, which, broadly speaking, is located between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth century BC. from C. It is the heyday of the Greek polis and of cultural splendor. This splendor is especially noticeable in sculpture, which laid the foundations for this art from then on.

The Greeks looked at the body and this, if it was beautiful, reflected a beautiful interior. The word for both qualities, like the two sides of the same coin, was kaloskagathos: beautiful on the inside and beautiful on the outside. Especially if he was a young man.

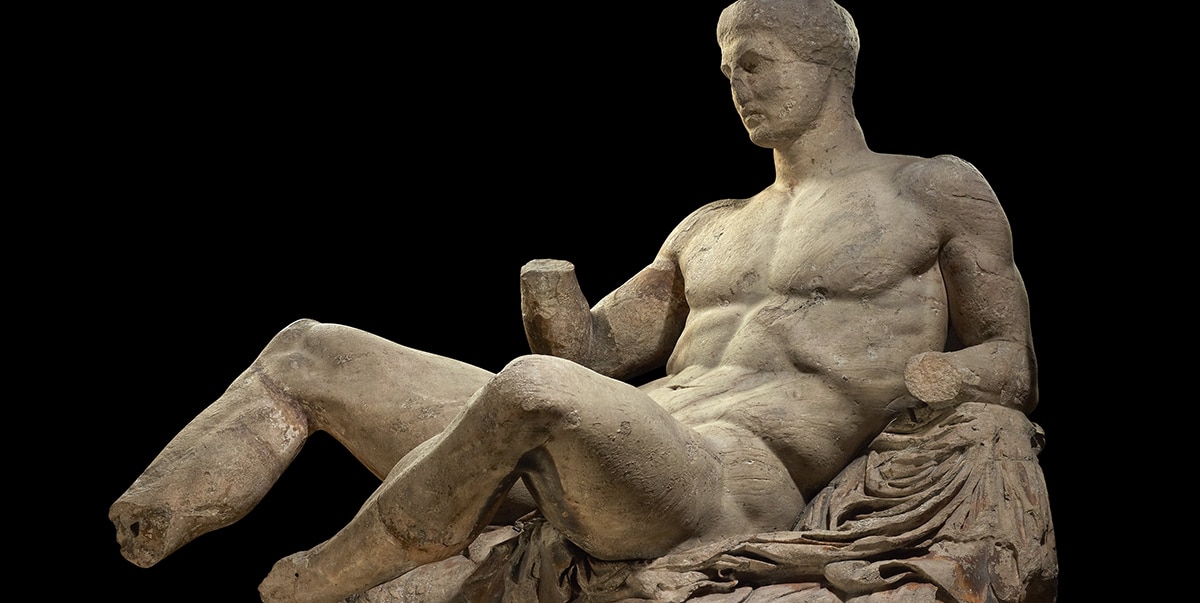

This line of thought was expressed in sculpture, the idea that a beautiful young man had been blessed three times, for his beauty, for his intelligence, and for being loved by the gods. For a long time it was thought that the sculptures of this period represented that idea, a fantasy, a desire, but the truth is that molds have been found, so today it is known that Those beautiful sculptures that were made between the XNUMXth and XNUMXrd centuries BC were based on real people.

A man was covered with plaster and the mold was later used to shape the sculpture. Greeks, we talk about the men spent a long time in the gym (If they were rich and had free time, obviously). An average Athenian or Spartan citizen had a body as sculpted as a Versace model: narrow waist, back, small penis and oily skin ...

That with respect to men, but what ideal of Greek beauty was that of women? Well, very different. If beauty in a man was a blessing, in a woman it was a bad thing. A beautiful woman was synonymous with trouble. kalon kakon, the beautiful and bad thing, could be translated. The woman was beautiful because she was beautiful and she was beautiful because she was beautiful. That line of thinking.

And it also seems that beauty implied competition: there were beauty pageants called callisteia, in which events took place on the islands of Lesbos and Tenedos where the girls were judged. For example, there was a contest in honor of Aphrodite Kallipugos and her beautiful buttocks. There is a story surrounding the search for a site to build her a temple in Sicily that was ultimately decided between the buttocks of two farmers' daughters: the winner chose the site to build the temple, simply because she had a better ass.

Perfect beauty

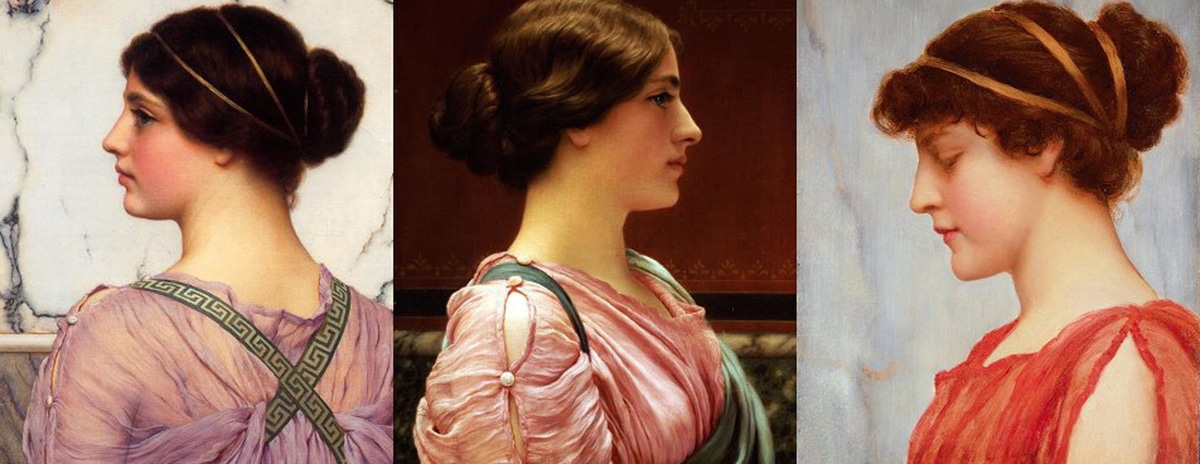

What is considered beautiful in Classical Greece? According to the murals and sculptures, a brief list can be made of what the ancient Greeks considered a beautiful body: the cheeks should be pink (artificial or natural), the hair had to be either shaved or neatly arranged in rolls, the skin should be clear y the eyes must have eyeliner.

The perfect body of a woman should be of wide hips and white arms, for which many times they were purposely bleached with powder. If the woman was a redhead, congratulations. It may be that in the Middle Ages redheads were the losers, through witchcraft and those strange things, but in classical Greece they were worshiped. The blondes? They didn't have a bad time either. In short, the goddess Aphrodite or Helen of Troy were synonymous with the ideal of beauty.

The idea of wide hips and white skin was actually kept for many centuries: a robust body is synonymous with good nutrition and therefore, a life with well-being. White skin is synonymous, in turn, with not being a slave or doing work outdoors but indoors.

But then, like today, being beautiful and having the perfect body involved a sacrifice. Few are born touched by the magic wand. The desire to keep skin white, or whiten it, led women to resort to methods that could affect their health.

One of the first comments on cosmetics in antiquity is precisely from that time. The Greek philosopher Teofastus de Eresos does so when describing how they made a lead-based cream or wax. Obviously, lead was and is toxic.

The use of makeup It was widespread in the upper class since everything served to exploit beauty, but there were several styles. The prostitutes had theirs and the women of good family, another. It was enough to see how the woman was made up to distinguish her, since the former used the most loaded eyes and the bright lips, dyed hair and more daring clothes. As usual.

What were the hairstyles in Classical Greece? The oldest examples of hairstyle in Greek women show them with braids, many and small. If we look at the pots, for example, you can see this style, but obviously with the passage of time the fashion changed.

It seems that around the XNUMXth century instead of wearing their hair down they began to wear it tied up, usually in a impeller. They also used ornaments and decorations various such as jewelry or something to show family wealth. Was the short hair? Yes, but it was synonymous with grief or low social status.

Of course, it seems that light hair was more precious than dark, so it was usual to use vinegar or lemon juice to clarify it in combination with the sun. And if they wanted curls, they made them and soaked them with beeswax so that the hairstyle would last longer. And what about the body hair? Were Greek women hairy like women have always been until the XNUMXth century?

Hair removal was common and in fact, not only among the Greeks but also in other cultures. At that time, in Classical Greece, not having hair was fashionable, although there are several theories about how they achieved hair removal. It is said that public hair was burned with a flame or shaved with a razor.

So if a woman traveled in time today, What products could not be missing in your dressing table? Olive oila for dry skin and if it was infused with aromatic herbs as it gave fragrance to the body or hair; miel in cosmetics, beeswax combined with rose water and a series of perfumes that were made with essential oils infusing oils and very fragrant flowers, carbon for the eyes, lashes and eyebrows and other minerals that, when ground, served as shadows and blushes.

One fact: the single eyebrow This was achieved by painting the line with charcoal or, if it was not enough, they glued animal hair with vegetable resin.

The perfect body

It is true that In Classical Greece, artists redefined the notion of bodily beauty in men and women inventing the idea of "Ideal body." The human body was, for them, an object of sensory enjoyment and expression of mental intelligence.

The Greeks understood that perfection does not exist in nature, it is provided by art. So there is the idea that a sculpted body is pure design. Above we said that Greek sculptors used real models, it is true, but sometimes it was not a single model, but several. For example, the arms of one, the head of another. Thus, a good compliment at that time was to tell a young man that he looked like a sculpture.

If Aphrodite was the ideal of feminine beauty, Heracles was the ideal of the perfect male body. Athlete, super man, representation of sex and desire. Like today with tattoos, the body art and weightlifting, then I was also looking at the body of others and my own.

Greek art was more focused on the male form than in the feminine and it is curious to see how, over time, art has followed an inverse path, focusing much more on women than on men. Let's think about the Middle Ages, the Renaissance or the Baroque forms.

On reflection, the debate about the body and beauty have always been in the limelight. From antiquity to today, from Nefertiti and Aphrodite, to the women of Rubens, Marilyn Monroe, the supermodels of the '90s and the celebrities of the XNUMXst century with plastic touch-ups, we continue to consider an ideal of the human body that is more for the other than for ourselves.

So, now you know, the next time you visit a museum and come across classic sculptures, look closely at those bodies and those of the people who move around you. The question is, when will we accept such and such nature made us?